Serverless authentication

You've got a feature that only a few people should use. How do you keep it safe?

Authentication.

It's easy in theory: Save an identifier on the client, send with every request, check against a stored value on the server.

In practice, authentication is hard.

Where do you save the identifier? How does the client get it? What authentication scheme do you use? What goes on the server? How do you keep it secure? What if you need to run authenticated code without the user?

Authentication is a deep rabbit hole. In this chapter, we look at the core ideas and build 2 examples.

What is authentication

A typical authentication system deals with everything from user identity, to access control, authorization, and keeping your system secure.

It's a big job :)

Identity answers the "Who are you?" question. The most important aspect of authentication systems. Can be as simple as an honor-based input field.

Access control answers the "Can you access this system?" question. You ask for proof of identity (like a password) and unlock restricted parts of your app.

Authorization answers the "Which parts of the system can you use?" question. Two schemes are common: role-based and scope-based authorization. They specify which users can do what.

Security underlies your authentication system. Without security, you've got nothing.

Typical concerns include leaking authentication tokens, interception attacks, impersonating users, revoking access, how your data behaves, and whether you can identify a breach.

Factors of authentication

Proof of identity is key to good authentication.

something the user knows, something the user has, something the user is

Each authentication factor covers a different overlapping proof of identity. 2 factors is considered safe, 3 is best. Typical is 1 🙈

Knowledge factors include hidden pass phrases like passwords, PINs, and security questions. You know the answer and verify the user knows too.

Ownership factors include ID cards, token apps on your phone, physical tokens, and email inboxes. You ask the user to prove they have something only they should have.

Inference factors include biometric identifiers like fingerprints, DNA, hand-written signatures, and other markers that uniquely identify a person.

Credit card + PIN is 2-factor authentication. You own the card and know the PIN.

Username + password is 1-factor. You know the username and know the password.

Passwordless email/sms login is 2-factor. You know the username and own the email inbox. Proof by unique link or pin.

Role-based and scope-based authorization

The 2nd job after access control is authorization. What can this user do?

Two flavors of authorization are common:

- role-based authorization depends on user types. Admins vs. paid users vs. freeloaders.

- scope-based authorization depends on fine-grained user properties. Enable subscriber dashboard or don't.

Technically they're the same – a user property. It's like utility vs. semantic classes in CSS. Debate until you're blue in the face, then pick what feels right :)

Role-based authorization is perfect for small projects. You need admins and everyone else. Being an admin comes with inherent rights.

Scope-based authorization is perfect for large projects with granular needs. Yes you're an admin, but admin of what?

In practice you'll see that roles get clunky and scopes are tedious. Like my dayjob gave me permission to configure CloudFront, but not to see what I'm doing. 🙃

At an organizational level you end up with roles that act as bags of scopes. Engineers get scopes x, y, z, admins can do so and so, and users get user things.

Build your own auth

Let's build a basic serverless auth designed to be used as an API. It's the best way to get a feel for what it takes.

I'll share and explain the important code. You can see the full example on GitHub. Use this CodeSandbox app to try it out.

You can test your implementation too. Change the Lambda base URL 😊

The auth flow

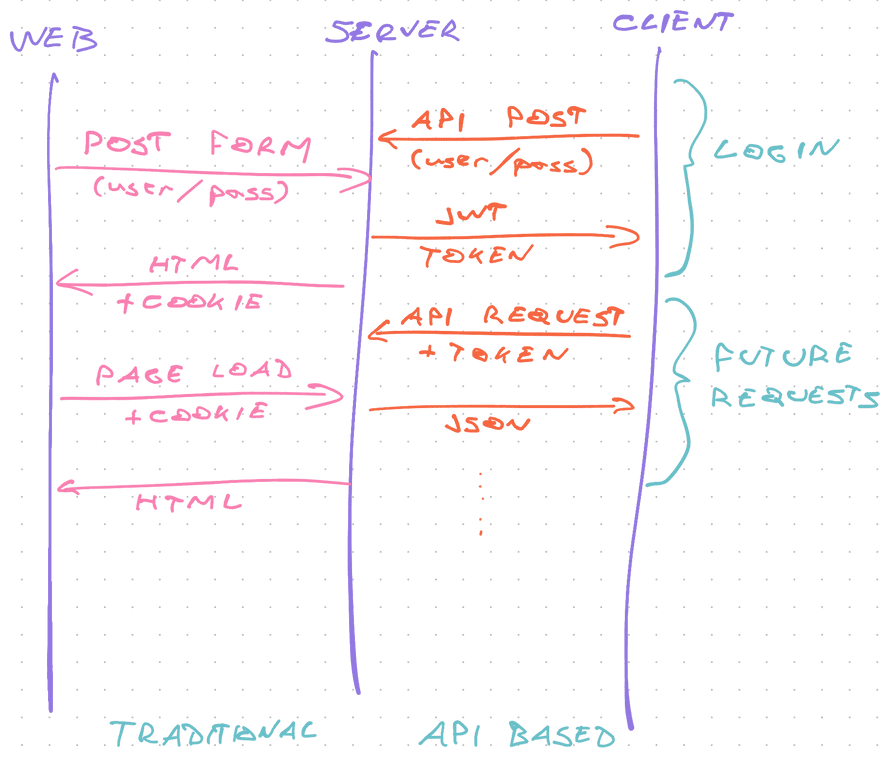

Traditional auth and API auth use a different medium to exchange tokens. Traditional auth uses cookies, API auth relies on JSON Web Tokens (JWT) and Authorization headers.

The API approach works great with modern JavaScript apps, mobile clients, and other servers.

- User sends username and password

- Server checks against database

- Returns fresh JWT token

- Client adds token to every future request

- Server checks token is valid before responding

This flow is secure because of the HTTPS encryption used at the protocol level. Without it, attackers could steal passwords and tokens by sniffing API requests.

Always use HTTPS and remember: A JWT token on its own lets you impersonate a user.

A note on password safety

You need to know the user's password to verify the user got it right. But never store a plain password.

A typical approach is to use a one-way hash. Feed password into a cryptographic function, get unique value that's impossible to reverse.

Since the invention of rainbow tables even one-way hashing is no longer secure. You can fight that with a salt.

// src/util.ts

// Hashing your password before saving is critical

// Hashing is one-way meaning you can never guess the password

// Adding a salt and the username guards against common passwords

export function hashPassword(username: string, password: string) {

return sha256(

`${password}${process.env.SALT}${username}${password}`

).toString()

}

Without a salt, the string password turns into the same hash for every app. Precomputed rainbow tables work like magic.

With a salt, the string password hashes uniquely to your app. Attackers need new rainbow tables, if they can find the salt.

Add the username and each hash is unique to your app and the user. Creating new rainbow tables for every user is not worth it.

That's when guessing becomes the easier approach. You can fight guessing with limits and timeouts on your login API.

Environment variables

We need 2 variables to build an auth system:

- a unique

SALTfor password hashing - a unique

JWT_SECRETfor signing JWT tokens

We define them in serverless.yml to keep things simple. Use proper secrets handling for production.

# serverless.yml

service: serverless-auth-example

provider:

# ...

environment:

SALT: someRandomSecretString_pleaseUseProperSecrets:)

JWT_SECRET: useRealSecretsManagementPlease

Never share these with anyone. JWT_SECRET is all an attacker needs to impersonate a user.

auth.login function

Users need to be able to login – send an API request with their username and password to get a JWT token. We'll keep it similar to the REST API chapter.

# serverless.yml

functions:

login:

handler: dist/auth.login

events:

- http:

path: login

method: POST

cors: true

We create a Lambda function called login that accepts POST requests and lives in the auth file.

// dist/auth.ts

// Logs you in based on username/password combo

// Creates user on first login

export const login = async (event: APIGatewayEvent) => {

const { username, password } = JSON.parse(event.body || "{}")

// respond with error if username/password undefined

// find user in database

let user = await findUser(username)

if (!user) {

// user was not found, create

user = await createUser(username, password)

} else {

// check credentials

if (hashPassword(username, password) !== user.password) {

// 🚨

return response(401, {

status: "error",

error: "Bad username/password combination",

})

}

}

// user was created or has valid credentials

const token = jwt.sign(omit(user, "password"), process.env.JWT_SECRET!)

return response(200, {

user: omit(user, "password"),

token,

})

}

We grab username and password from request body and look for the user. findUser runs a database query, in our case a DynamoDB getItem.

If the user wasn't found, we create one and make sure to hashPassword() before saving.

If the user was found, we verify credentials by hashing the password and comparing with the stored value. We know passwords match when the hashPassword() method creates the same hash.

This means you can never change your

hashPassword()method unless you force users to reset their password.

Then we sign a JWT token with our secret and send it back. Make sure you don't send sensitive data like passwords to the client. Even hashed.

// user was created or has valid credentials

const token = jwt.sign(omit(user, "password"), process.env.JWT_SECRET!)

return response(200, {

user: omit(user, "password"),

token,

})

We're using the jsonwebtoken library to create the token.

You can try it in the CodeSandbox. Pick a username, add a password, see it work. Then try with a different password.

auth.verify function

For authentication to work across page reloads, you have to store the JWT token. These can expire or get revoked by the server.

Clients use the verify API to validate a session every time they initialize. A page reload on the web.

When you know the session is valid, you treat the user as logged in. Ask for a username/password otherwise.

serverless.yml definition is almost the same:

# serverless.yml

functions:

# ...

verify:

handler: dist/auth.verify

events:

- http:

path: verify

method: POST

cors: true

Function called verify that accepts POST requests and lives in auth.ts.

// src/auth.ts

// Verifies you have a valid JWT token

export const verify = async (event: APIGatewayEvent) => {

const { token } = JSON.parse(event.body || "{}")

// respond with error if token undefined

try {

jwt.verify(token, process.env.JWT_SECRET!)

return response(200, { status: "valid" })

} catch (err) {

return response(401, err)

}

}

Verifying a JWT token with jsonwebtoken throws an error for bad tokens. Anything from a bad secret, to tampering, and token expiration.

private.hello function

This is where it gets fun – verifying authentication for private APIs.

We make an API that says hello to the user.

# serverless.yml

functions:

privateHello:

handler: dist/private.hello

events:

- http:

path: private

method: GET

cors: true

Function accepts GET requests and lives in the private.ts file. It looks like this:

// src/private.ts

export async function hello(event: APIGatewayEvent) {

// returns JWT token payload

const user = checkAuth(event) as User

if (user) {

return response(200, {

message: `Hello ${user.username}`,

})

} else {

return response(401, {

status: "error",

error: "This is a private resource",

})

}

}

The checkAuth method takes our request, verifies its JWT token, and returns the payload. A user in our case.

If user is authorized, we say hello, otherwise return an error.

checkAuth is where we read a token from the Authorization header and verify it looks good.

// src/util.ts

// Used to verify a request is authenticated

export function checkAuth(event: APIGatewayEvent): boolean | User {

const bearer = event.headers["Authorization"]

if (bearer) {

try {

const decoded = jwt.verify(

// Bearer prefix from Authorization header

bearer.replace(/^Bearer /, ""),

process.env.JWT_SECRET!

)

// We saved user info in the token

return decoded as User

} catch (err) {

return false

}

} else {

return false

}

}

The Authorization header holds our token – Authorization: Bearer <token>. If the header is empty, return false.

The jwt.verify() method verifies the token was valid. Checks that it was created with our secret, wasn't tampered with, and hasn't expired.

verify decodes the token for us, which means we can see the user's username without a database query. 🤘

Use an auth provider

An auth provider like Auth0, Okta, AWS Cognito, Firebase Auth, and others makes your integration more complex. But you don't have to worry about password security and user management.

And if a big provider gets hacked, your app is one among thousands. Feels less bad eh? 😇

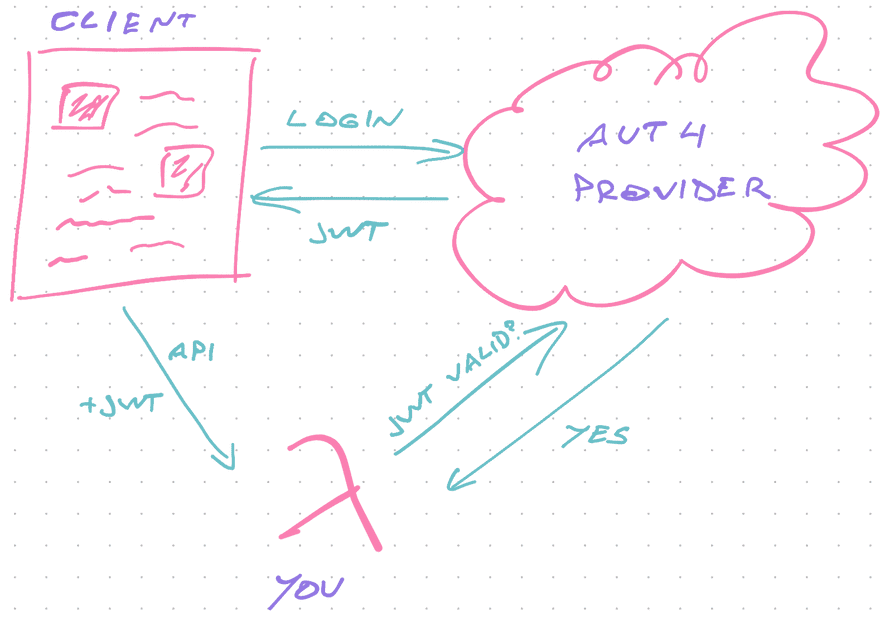

The key difference with a provider is the 3-way trust model. Users authenticate with a provider and send you a JWT token.

But you're not the authority.

That means a login dance between your server and the auth provider. You'll need to send your own JWT token to ask if the user's token is valid.

Exact integration depends on your provider of choice. I recommend following their documentation.

If performance is critical, this option is not great. You're adding API requests to every private call.

An example integration

Here's what I do to create users on Auth0 when you purchase a course on Gumroad, a payments provider. It's the provider <> lambda part of the flow.

The course platform runs in the browser, which means the user <> lambda connection wasn't necessary. A benefit of using a provider 😊

Gumroad sends a POST request to AWS Lambda on every purchase. It runs this function:

export const pingHandler = async (

event: APIGatewayEvent

): Promise<APIResponse> => {

const ping: GumroadPing = qs.parse(event.body!) as any;

if (ping.product_permalink in PRODUCTS) {

// create user from Gumroad data

const user = await upsertUser(ping);

if (user) {

// initialize Auth0 server client

const auth0 = await getAuth0Client();

const roleId = PRODUCTS[ping.product_permalink];

// give access to the course

await auth0.assignRolestoUser(

{ id: user.user_id! },

{

roles: [roleId],

}

);

}

}

return response(200, {});

};

The function parses data from Gumroad, creates a user on Auth0, and assigns the right role. I treat roles as scopes 👉 which courses can this user access?

Auth0 Client

Getting the Auth0 client means authenticating the server through a shared secret. Like a username and password.

async function getAuth0Client() {

const secrets = await auth0Tokens();

const auth0 = new ManagementClient({

domain: `${secrets.domain}.auth0.com`,

clientId: secrets.clientId,

clientSecret: secrets.clientSecret,

scope: "read:users update:users create:users",

});

return auth0;

}

getAuth0Tokens talks to AWS Secrets Manager to retrieve secrets. We feed those to a new ManagementClient, which will use them to sign JWT tokens for future requests.

Auth0 will be able to jwt.verify() to see that we know the right secrets.

A ManagementClient can manages users. For authentication you'd use the AuthenticationClient.

We ask for as little permission as possible. If someone steals these secrets, or the code, they can't do much.

If an attacker tries to expand permissions, Auth0 config says "hey this client can't do that even if it asks"

Create user

Creating a user is a matter of calling the right methods. Look for user, create if not found.

async function upsertUser(purchaseData: GumroadPing) {

const auth0 = await getAuth0Client();

// find user

const users = await auth0.getUsersByEmail(purchaseData.email);

// create if not found

if (users.length > 0) {

return users[0];

} else {

return auth0.createUser({

// user data

});

}

}

What approach to choose?

Hard to say.

Building your own is fun the first 2 or 3 times. User management and authorization is where you go ouch and think "I have better shit to do damn it".

Libraries help :)

An auth provider has more engineers to think about these problems and give you a nice experience. But integration is more complex.

Whatever you do, don't build your own cryptography. ✌️